Singular artists, almost by definition, work against the prevailing mood of the artistic moment; frequently they revisit a supposedly outmoded visual style or employ a method or technology no longer deemed viable. The recent gouaches of Bill Schmidt and his earlier sculptures contain a strong biomorphic impulse, a type of imagery and buried content so strongly connected with European surrealism that it has spent the past few decades out in the wilderness, banished from contemporary art by abstract expressionists, Pop-ists and hard-core minimalists alike. Surrealism was the 1940s movement that Pollock came from, not the destination towards which he was headed, it was the style associated with well-behaved European abstractionists like Arp and Tanguy, a pictorial tic at odds with the American emphasis on self-expression, angst and size or its supposed opposite, emotional reserve and factory finish. Biomorphism was too dream-oriented, too Freudian, too polite. In the 1950s, those artists still drawn to biomorphic shapes saw their reputations permanently damaged or their public reception delayed for years. Take for example Gabor Peterdi’s obsessive etchings and engravings (he’s only a technician, a teacher!), the subaqueous paintings of Baziotes (Uptown minor expressionist!), the sculptures and drawings of Louise Bourgeois (she’s really French!), or the strange little boxes Cornell was fabricating in a domestic environment on Utopia Parkway in Queens (who knew?). This prejudice against the biomorphic has loosened up somewhat in our polymorphous new century, though even Terry Winters has moved away from his natural inclination. The much more important art of Elizabeth Murray, an artist who chose to use the organic despite having been educated in the heyday of Minimalism and Post-Minimalism, is still marginalized by the critical mainstream.

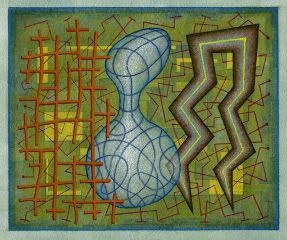

Born in Trenton in 1947, Schmidt was educated at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Maryland Institute College of Art where he has taught for many years. There is a modesty and uprightness to his physical being and emotional aspect that has almost vanished from the American scene, let alone in the cavernous spaces of Chelsea. Like a frontiersman, Schmidt does many things well; he has a self-sufficiency that is striking. In addition to being an expert refinisher of furniture and a gilder, he is a fine musician who plays traditional American music on banjo, fiddle, ukulele and guitar. After more than two decades as a maker of objects others would call “sculpture”, a residency in Rochefort-en-Terre, France, returned him to his roots as a painter. All of the paintings in this show were made with gouache (opaque watercolor) and executed in the last two years. Many of them have additional markings of colored pencil and water-soluble crayon. That they are intimate in scale is of greatest importance; the largest painting is only 7 x 5 inches while the smallest is two and a half inches square. And though Schmidt is a student of Persian miniatures and manuscript illumination, his abstractions clearly channel the work of Paul Klee, the one great Modernist who almost always worked in small scale. Schmidt develops a repertoire of shapes and figures, transferring them with tracing paper into other formats, situating them in a universe of shifting planes and uncertain space. “Lineup” seems the closest to Klee in shape and format, assembling three “personnages” across a plaid landscape of roses and yellows. Like miniature upright sculptures, each shape has a unique identity and is read as human by the anthrocentric eye of the viewer. Though the space behind them is ambiguous, the crossing lines forming and re-forming myriads of cells, the three shapes are free to interact even if they never will. Something similar happens in “Small Plaid Universe”, the very title of which discloses the somewhat larger ambitions Schmidt has for the import of his work. Here the shapes almost look like Indian arrowheads (cf. Steven Wheeler) arrayed on a blanket, little jagged lines of cosmic energy disrupting the well-behaved cells, some of which have affinities with the Constellations of Joseph Albers. The action takes place on a small green stage or Klee-like pedestal drawn at the bottom of the composition.

In “Hokum”, Schmidt’s little universe gets a bit unruly, yellow, green and pink diagonals and jagged lines of blue replacing the minimalist regularity, little bits of cosmic “strings” arrayed in hoops entwining the single biomorphic shape. A general increase in the number of components leads to further spatial complexity; this is also seen in “Ends Against the Middle”, a work in which the top and bottom shapes collapse against the middle. Schmidt’s doodling reaches a manic intensity in “On A Tiny Planet”, a painting almost subaqueous in its greenish skein of nets and barbed wire fences (cf. Baziotes), portraying an environment in which a tan personnage with orange highlights battles a multi-armed yellow and red creature, the whole of which looks nothing so much like a computer circuit board, and the teasingly-named “One of These Things Is Not Like The Other”, a painting in which Schmidt’s entire cast of characters seem to take a bow. The music of the avant-garde composer Conlon Nancarrow inspires a similarly complex landscape of microscopic creatures afloat in a cubist petri dish. The beautiful outlier in the show, the little painting called “It Ain’t a Sin to Shed Your Skin”, is an almost perfect tribute to the art of Elizabeth Murray. The single figure of red and yellow recalls the layering of her fractured planes, the background stripes the influence of Frank Stella on her art, the pincers on each side (and the title) the difficulty of moving on from one phase of life to another. That the impulse for such intellectual and technical play reaches back to Paul Klee, not to mention the light washes of color hidden in the interstices of each piece, is not surprising.

Though abstract and of modest scale, the wall-hung sculptures of Bill Schmidt occupy an almost opposite visual extreme to that of his paintings; monochromatic and hieratic, they are more formal, though not without their humorous moments. The two bodies of work almost look like a group show of at least two artists or a family gathering of distant cousins. Nevertheless, the sculptures share with the drawings an interest in biomorphic shape and the interiority of space; many of the sculptures are cages surrounding voids like African masks, not unlike the interstices of the drawings. In his sculptural objects, Schmidt is naturally less interested in the issue of interior light than how the forms penetrate the real space around them. Insistently vertical, Schmidt’s structures share a family resemblance with the personnages of Louise Bourgeois. Despite their deceptive simplicity, his sculptures may offer a more reliable self-portrait of the artist in abstentia than does more conventional work incorporating an artist’s actual presence. A woodworker and enthusiastic camper, and an outwardly reserved, compulsive perfectionist, Schmidt shares the sly humor and decidedly vertical extension of his sculptures. But Schmidt’s voice may not be the only one speaking in these works, conflicted as they are between the useful and the useless; in them, we hear an entire chorus of discarded Americana and nostalgia for the verities of Art Deco. That they are light to the hand and made of wood is not incidental; Schmidt’s sculptures share the quiet assurance of organic growth one sees in all his work. Between the drawings and the sculptures we are immersed in a forest of signs for our social and solitary selves, upright creatures moving through the world, sensible to the microscopic world that moves within us. An artist of his time who has assumed a stance outside of time, Schmidt’s contemplative art reveals the interpenetration of experience from the atomic through the personal to the cosmic like that of almost no one else I know.

- Dr. Michael Salcman

No comments:

Post a Comment